I spent a terrific week in Boston for the 2015 NCSM & NCTM conferences. I am recapping the NCSM sessions here. I already summarized the NCTM sessions in a previous post.

I spent a terrific week in Boston for the 2015 NCSM & NCTM conferences. I am recapping the NCSM sessions here. I already summarized the NCTM sessions in a previous post.

As with my other Re-Cap, I have summarized each session with some simple (•) bulleted notes and quotes to encapsulate my major take-aways, and occasionally a brief italicized commentary.

While I have been to several NCTM conferences, this was my first NCSM trip. For my new position as math coach, this was experience was very worthwhile.

What the Research Says About Math Coaching? — Maggie McGatha

Positive, small student increase in 1-2 years, strong spikes after 3-4 years.

Positive, small student increase in 1-2 years, strong spikes after 3-4 years.

Math Coaching works, but you must be patient. This was my biggest, most encouraging take-away of the conference.- Positive teacher growth on incorporating Questioning, Engagement, Conceptual Understanding, Group Work, Discourse & Technology.

- Spectrum of Coaching

(least directed is most effective, all are needed)

most directed ——————————- least directed

Model lessons Co-Planning Data Reporting

Resources Co-Teaching Reflecting

Ironically, the most directed (lesson resources) is what teachers request most often, even though it was the least effective service from math coaches. It still showed teacher growth and student improvement, so this is the logical place to start with teachers. As soon as possible, though, it is better to work side by side with the teachers on these lessons. The ultimate coaching service, though, appears to be the debrief… having teachers look at student results and contemplate their effect on student learning.

Achieving Equity: Instructional Strategies to Reach All Students (Chicago) — Ruth Seward, Jessica Fulton, Lynn Narasimham

The third largest district in the country has a very structure, organized, intentional professional developement program.

The third largest district in the country has a very structure, organized, intentional professional developement program.

If a district this large can provide sustained PD for its teachers, then my district should be able to do the same. We just need a plan and a system to implement it. My district has both, but they need to be revisited to include some of the following.- Focus on Engagement, Application and Communication

- Accountable Talk… Just as teachers should question more than tell, we should have students do the same with each other, also.

- 3-Reads by Harold Asturias

1) Read aloud to a peer.

“What is the problem about?”

2) Read the problem again.

“What is the question in the problem?”

3) Read it a third time.

“What information do you know and not know?” - Hierarchy of training:

Facilitators ->Teacher Leaders -> Teachers

PD is given to Admin as well as Teachers.

PD for teachers includes Elbow Coaching (Co-Planning, Co-Teaching, Co-Reflecting) - The Five Dimensions of Mathematically Powerful Classrooms

- We were also shown an example of the types of activities that are promoted in their teacher training. We were asked to place the Decimal/Percent cards in order from least to greatest, and to fill in any blanks. Then we had to match the set of Fraction cards, followed by the Area Model cards, and finally the Number Line cards.

This would be a great activity to open the year with in ANY class, even an upper level, in order to accelerate number sense and set norms for group work.

Engaging ALL Learners in Mathematical Practice through Instructional Routines — Amy Lucenta & Grace Kelemanik of the Boston Plan for Excellence

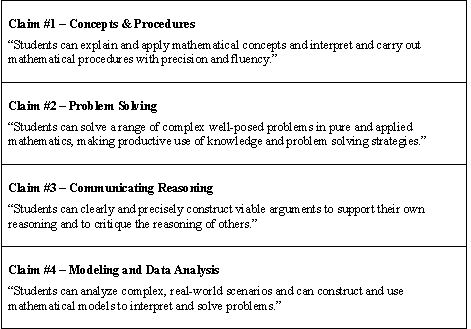

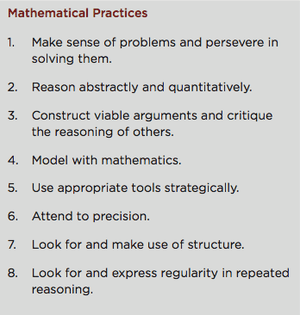

The Standards for Mathematical Practice create open doors to struggling students, not walls.

The Standards for Mathematical Practice create open doors to struggling students, not walls.

This is such a simple, yet profound concept. It was the heart this presentation, and one of the best principles pitched at the conference. I’m a fan, because it is one of the three principles that I shared in my presentation at NCTM .

- Not all SMPs are created equal. #1, followed by #2, 7, 8.

I have heard many people say that the 8 Practices should be a shorter list. It was interesting to see their list.

Hey! What’s the Big Idea? — Greg Tang

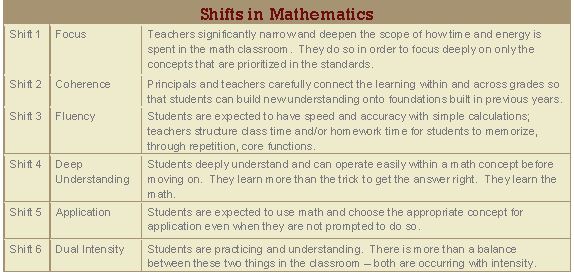

Progressions is the Big Idea?:

Progressions is the Big Idea?:

Concepts -> Algorithms -> Speed

Greg really pushed for a balanced, reasonable approach to teaching math. I have always emphasized the first two, but was challenged to put more effort into the back end. This was one of the Biggest Ideas that I brought home.- Number Sense is Key, and can be enhanced through number games.

I am now addicted to Kakooma - “Generalizing your thinking is what makes you smart.”

Reinventing Algebra in a Common Core World — Eric Milou

Provocative Statement #1: Dr. Milou laid out an Algebra sequence that pushed the introduction of Quadratic functions to Algebra 2.

Provocative Statement #1: Dr. Milou laid out an Algebra sequence that pushed the introduction of Quadratic functions to Algebra 2.- Provocative Statement #2: Teachers need to to start a grassroots revolution to address the Common Core’s failure to limit the bloated list of standards in high school, since no revision/feedback mechanism exists.

I was very impressed that NCSM allowed a dissenting view, and I loved the courage with which Dr. Milou spoke. While I find his suggestion having merit in terms of math progressions, I don’t see how it addresses the glut of standards, so I agree with him that there needs to be a feedback mechanism to address that issue.

Sense-Making: The Ultimate Intervention — Janet Sutorius

- Removing the mathematics from context and focusing on procedures prevents students from using their own common sense and sense-making abilities to do mathematics. Struggling students need a contextual framework the most.

I have always said… naked math comes last.

Hot Topics: Intervention — Matt Larson

Do not pull struggling students out from class. Give them additional learning, instead.

Do not pull struggling students out from class. Give them additional learning, instead.

This was a round table discussion with a big name in the field of math ed. He described some field studies he was involved with in Chicago regarding elementary intervention structures. The big take-away here was to not have intervention students miss class time. Build the time into the day when they receive additional instruction on unmastered topics, and give those who have mastered the topic an enrichment activity.

Occam’s Razor — Eric Hart

Focus on the Math first (methodology second)

Focus on the Math first (methodology second)

This echos what I learned from William Schmidt, about focusing on the mathematics, not the methodology.- “If we could switch from telling to questioning, we would change the world of math education.”

A college Professor said this! In public! I pressed him on this statement, which I whole-heartedly agree with, but pointed out the obvious … college math is taught almost entirely through telling. His response was, “That is changing.” - Which form of the Quadratic Formula is better? Doesn’t the less conventional one make more conceptual sense?

This pic got a lot of response on Twitter.

- Students in other nations do not spend as much time on factoring as U.S. students. They use the Quadratic Formula to get factors them plug them into the equation.

Mathematic Modeling with Strawberries and Video — Sean Nank

Mathematic Modeling with Strawberries and Video — Sean Nank

- Sean had us participate in a modeling task that involved a video of himself cutting strawberries. The task walked us through each step of the Common Core’s definition of modeling:

- Identifying variables,

- Formulating a model by creating and selecting representations that describe relationships between the variables,

- Analyzing and Performing operations on these relationships,

- Interpreting the results of the mathematics in context,

- Validating the conclusions,

- Reporting on the conclusions and the reasoning behind them.

The question was simple, “How long will it take to cut the strawberries?” The task, however, was rich and robust. While Dr. Nank allowed the lesson to be very student driven, he still paused before each of the 6 steps above, to direct us in the next segment. It was a great demonstration of how to scaffold the teaching of modeling, instead of the typical errors of “Here kids, now model.” or the “Let me show how modeling is done.”

Marilyn Manson Pedagogy: “Just shut up and listen.”

Marilyn Manson Pedagogy: “Just shut up and listen.”

Dr. Nank shared an interesting anecdote. He said after the Columbine shooting, Marilyn Manson was asked what he would say to the kids. He claimed that he wouldn’t tell them anything, he would “just shut up and listen.” Sean was encouraging us to do the same while the students are working on the various components of modeling.

PAEMST Seminar for Awardees of The Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching — Dan Meyer

Dandy Candy Lesson

Dandy Candy Lesson

I have always loved this task. Dan took it so much deeper than I had imagined from his post on it. It was a delicious pleasure to participate in it with its creator.

The conversation at my table of instructional leaders was how to get teachers to do lessons of this richness and quality. Our teachers back home all readily admit that they need as much scaffolding in teaching these kind of lessons as the students do in learning them.- When leading students through a task like this, wait for their questions. “Don’t give away too much, too soon. You can always add, but you cannot subtract.”

- Dan shared Sean Nank’s/Common Core’s Definition of Modeling. (He also has a great post on modeling.)

Dan also probed us for our take on it. There was consensus at my table that the definition was solid, but that modeling did not always have to be that comprehensive or limiting. There was also consensus that creating mathematical models from a given context to this degree needs to be done far more often in classes.

I once again I saw Sean Nank. Turns out that he is a 2009 awardee. He announced to the gathering that Volume 2 of The Making of a Presidential Mathematics and Science Educator is in the works.

I once again I saw Sean Nank. Turns out that he is a 2009 awardee. He announced to the gathering that Volume 2 of The Making of a Presidential Mathematics and Science Educator is in the works.

I met up with Jerry Young of Oregon, a fellow awardee from 2001 whom I really connected with in Washington DC, some 13 years ago. This was a treasured highlight of the trip.

I met up with Jerry Young of Oregon, a fellow awardee from 2001 whom I really connected with in Washington DC, some 13 years ago. This was a treasured highlight of the trip.

As you can tell, it was a great trip, from which learned a great deal. I am already looking forward to NCSM 2016 in San Francisco.

D

D